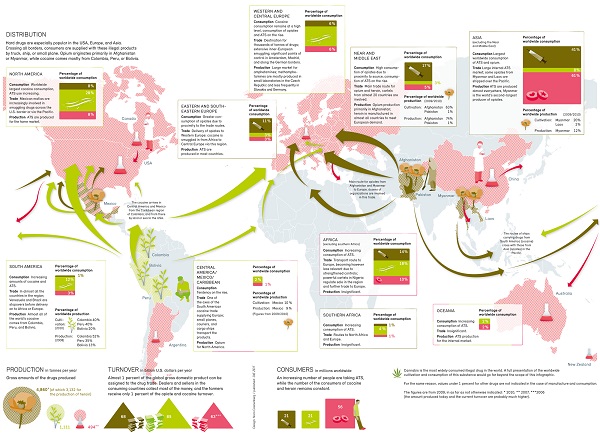

Several Canadian, Dutch and British companies are in play in the global cannabis export market. Today, the U.S. accounts for more than 90% of all legal sales of this product. It begs the question, will the countries historically involved in cannabis production be able to hold their own in this competition?

Cannabis is a universal resource

Cannabis is a crop that mankind has been growing together for many thousands of years (at least ten thousand according to some reports) and that people have worked together to improve and spread around the world. At its core, it is a public resource.

Attempts to restrict its trade, ostensibly out of concern for public health, on detailed analysis often come to light as economic manipulation designed to enrich some at the expense of others.

The UK is a good example: it is currently the world’s leading producer and exporter of medical cannabis, while the general population faces severe restrictions on access to medical cannabis.

The CEO of the nation’s largest enterprise (British Sugar), which focuses on vulnerability, protection and countering extremism, has a full history of actively opposing cannabis legalization (Paul Kenward, and his wife, Victoria Atkins).

He says:«It is important to ensure that the enormous potential value of this common global resource is distributed to people in the most equitable way possible. The development of an increasingly connected global economy, distinguished by free trade and the free movement of capital, is not fundamentally a negative phenomenon. Strengthening social, cultural and economic ties among people can bring many clear benefits».

«Globalization» has helped the spread of cannabis

The basic idea behind globalization is not fundamentally negative. The strengthening of social, cultural and economic ties between people can bring many obvious benefits.

Globalization is not a new phenomenon. For centuries, people have traveled great distances and formed many stable trade networks covering vast areas around the globe. The Silk Road exemplifies a historical and almost global network that stretched thousands of miles across Asia, deep into Europe and Africa, and existed for more than a thousand years.

The Silk Road remains relevant because it likely contributed to the spread of cannabis from its original locations in Central and South Asia to West Asia, Africa and Europe.

Cannabis (in the form of seeds, fibers, fabrics, oils, ganja and hashish) has been a «global» product for centuries, and without such extensive ancient trade networks its distribution would not have been as wide.

The next industry is «Corporate Cannabis»

Of course, the Silk Road also allowed Genghis Khan’s huge Mongol horde to plunder Eurasia, defeating the various armies that opposed it.

Even so, our modern and highly sophisticated trading networks allow large corporations to exploit vast areas of the planet, but with few restrictions to limit their insatiable growth and consumption, with a number of highly sophisticated technological devices to effectively accomplish their tasks, as well as the support and encouragement of national governments.

All of the above has the potential to increase the suffering of the population at large, while enriching an increasingly small elite to an unprecedented degree.

The cannabis industry, unfortunately, is not immune to this effect. Advantages for large corporations almost inevitably lead to disadvantages for small producers, both at home and abroad. In California, hundreds of small cannabis producers are at risk of losing their livelihoods as the recent legalization of the recreational market facilitates the influx of corporate money.

In both Oregon and California, cannabis surpluses have caused prices to plummet to $100 a pound; dozens of cannabis producers have been bankrupted, with the largest and best-funded businesses apparently best able to weather the storm. Internationally, the growth of giant multinational cannabis companies has begun, and so far they are largely owned by the West.

Great Britain, Canada and the Netherlands are now the world’s largest exporters of legal cannabis; New Zealand, Australia, Israel and Uruguay (all usually considered «Western» in terms of socio-economic status) seem likely to join them in the near future.

Cannabis monopolies in the past

Cannabis is a plant that has unique properties that have piqued people’s interest throughout history. However, many governments have restricted its use or sale, and these restrictions have often been followed by government monopolies on trade in the plant. An example of this phenomenon is the context of European colonialism, where pre-colonial Morocco and Ottoman Tunisia offered monopolies on their domestic industry.

After Spain and France took control of Morocco in 1912, France maintained a monopoly on cannabis until independence in 1956. Similar attempts to control the cannabis trade have been made in various parts of the world, including the Maghreb, South Africa, Central Africa, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Australia and China. In these regions both opium and cannabis were sold under the monopoly of the Dutch and British East India companies. Cannabis has many health benefits and can be used for medicinal purposes.

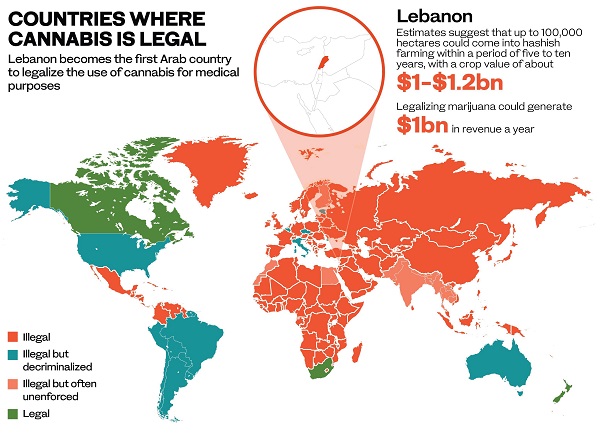

Cannabis is already legal in some countries for medical use and in some for recreational use. However, despite all of these beneficial properties, cannabis is still illegal in many countries, and its use or sale can lead to serious legal consequences. Therefore, before using cannabis, be sure to familiarize yourself with the laws of your country.

There are also many examples of countries that severely limit the number of licensed cannabis producers, effectively creating oligopolies (markets dominated by a few companies).

Examples include Israel, Canada, and many countries that have only introduced medical legislation in recent years. With this trend, legal marijuana is slipping out of the hands of the general public and becoming the domain of a small handful of business elites.

It goes without saying that restricting access to legal cannabis to the 300 million citizens of the world who use it regularly will do little to suppress the power of the illegal market.

Is monopoly the right approach to solve the problem?

Uruguay has established a state monopoly on cannabis, although the commitment to establishing a low retail value suggests that its objective may be somewhat more altruistic than most other states. In addition, national legislation includes the right of all citizens to grow a certain amount of plants for personal use.

However, the current situation is far from perfect. There have been appeals to the quality of cannabis available, the monthly limit of 40 grams imposed on each person, and concerns about the requirement to register with the authorities and give a fingerprint before gaining access to cannabis. State registration is also required for domestic producers, and only a few thousand of the state’s 3-4 million inhabitants are currently registered.

Moreover, Uruguay is actively pursuing plans to export CBD oil as medicines. Its laws do not allow commercial, commercial exports of medicinal cannabis products. Thus, there is criticism that licensed growers are focusing too much on the more profitable cultivation of high CBD cannabis while not supplying enough cannabis with high THC content.

Major nations are breaking common laws

Almost a century has passed since the first international laws were enacted that prohibited the use of cannabis, and now these same laws are facing a steady trend toward its legalization.

Nine U.S. states now allow the sale of cannabis for recreational purposes, even though it is still considered illegal at the federal level. Uruguay and Canada were the countries that legalized the sale of cannabis for recreational purposes, with Uruguay doing so in December 2013 and Canada in June 2018.

The response of the United Nations and the International Narcotics Control Board (which is an independent and quasi-judicial body that oversees the UN drug conventions) has been relatively weak and has so far been limited to a few sweeping statements.

Almost a century after the first international laws against the use of cannabis were introduced, these same laws have faced a steady trend toward its legalization.

Nine U.S. states now allow the sale of recreational cannabis, even though it is still illegal at the federal level. For recreational purposes, cannabis was legalized in Uruguay in December 2013 and in Canada in June 2018.

The response of the United Nations and the International Narcotics Control Board (an independent and quasi-judicial body that monitors compliance with the UN drug conventions) has been relatively mild and has so far been limited to a few harsh statements.

Uruguay has chosen to simply ignore the violation of its treaty obligations without abandoning the treaty or seeking compromise; Canada is now in breach of the treaty, and it is unclear what path it will take in its future relations with the UN. This approach will undoubtedly influence the strategy the U.S. chooses.

Traditional cannabis centers are again at a disadvantage

Many countries around the world, faced with repeated economic and military sanctions or international isolation for violating UN conventions, should not react harshly to violations of international treaties. The recent UN conflict over breastfeeding is a prime example of how powerful countries can easily impose their will on others by threatening to withhold military support.

Regarding cannabis, many countries continue to enforce measures against the illegal trade, including forced eradication programs. In general, the responsibility for controlling illicit drug production and trade rests with national governments. Drug producing countries must implement eradication or other programs, or they risk international sanctions, possibly in the form of a withdrawal of military aid.

As a result, many cannabis-producing countries are very cautious about violating any international treaties because of the experience of past sanctions. At the same time, other, more powerful countries can violate treaties with impunity, setting up businesses and profiting from a commodity that traditional producing countries still have limited access to.

Efforts to redress imbalances in the global cannabis industry

To be sure, the situation is not easy. Colombia, which for decades has experienced the most brutal and aggressive methods in the world war on drugs, intends to resume its deadly aerial eradication operations against large coca plantations this year, under U.S. pressure.

However, Colombia is also actively working to legalize medical cannabis and create a legal regulated market (fourteen licenses have been issued so far). The country plans to begin exporting in 2019, even though it will have to fight strong competition.

Many other traditional producing countries are actively adopting modern methods of cannabis production. India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey, Lesotho, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Greece, Mexico, Jamaica and several other countries have passed various forms of cannabis legislation in recent years.

However, a more detailed analysis of the ownership of licensed companies shows that this does not necessarily lead to a global imbalance. In Lesotho, for example, five licenses are owned (in whole or in part) by American, British and Canadian companies. Three of them are wholly foreign-owned, the other two are 30% and 10%, respectively.

The Future of Cannabis Around the World

Countries with less developed economies may have the potential to compete with Western players in the global market. Most traditional cannabis producers are located in regions of the Global South where favorable climatic conditions and relatively low production costs facilitate cannabis cultivation.

Colombia, for example, uses its unique climatic conditions, including a 12/12 year-round light cycle and stable temperatures, as key advantages for growing cannabis, allowing for year-round flowering and multiple harvests. India, as the historical center of cannabis, has unmatched genetic diversity and ideal conditions for many local varieties to thrive.

In contrast, Canada, Great Britain and the Netherlands are northern countries with short, cool summers and limited natural potential for cannabinoid production. Most of their medical cannabis is grown indoors, which entails significant financial and environmental costs.

However, in order for traditional producers to gain an advantage in the global marketplace, it will likely require competition from large corporations. In this context, the growing influence of corporations around the world may pose a threat to small producers.