Bipolar depression, a challenging and often debilitating aspect of bipolar disorder, poses significant hurdles for those affected by the condition. Traditional treatment methods, while effective for many, may not fully address the complexities of bipolar depression, leaving some individuals with limited relief from their depressive symptoms. In recent years, a growing interest in alternative and innovative approaches to mental health treatment has sparked a renewed curiosity in the potential benefits of microdosing psychedelics for bipolar depression.

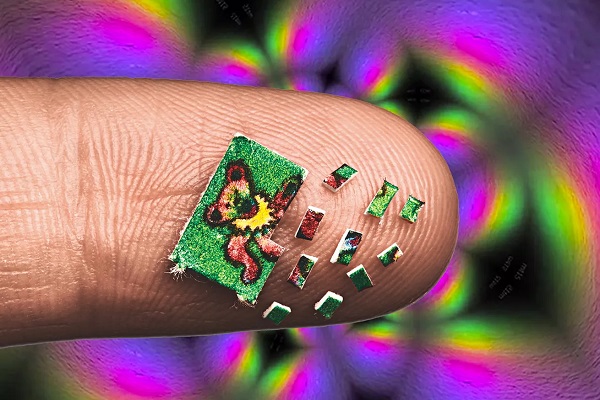

Microdosing, a practice that involves taking minute sub-perceptual doses of psychedelic substances, has gained traction as a potential therapeutic avenue for various mental health conditions. Advocates suggest that this practice could offer a unique perspective on managing bipolar depression, offering relief from depressive symptoms without inducing the intense and potentially destabilizing effects of full psychedelic experiences.

The psychedelics under investigation include substances like LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), psilocybin (found in “magic mushrooms”), and DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine). These compounds have shown promise in addressing other mental health disorders, such as treatment-resistant depression and anxiety, leading researchers and individuals to question whether they may hold promise for those navigating the complex challenges of bipolar depression.

This article delves into the intriguing world of microdosing psychedelics as a potential adjunctive therapy for bipolar depression.

Psychedelic substances

Psychedelics, a captivating class of psychoactive substances, have fascinated humanity for centuries. Within this diverse group, two prominent categories exist: classic and atypical psychedelics. Each class elicits distinct experiences and altered states of consciousness, shaped by unique pharmacological mechanisms.

Classic psychedelics, also referred to as hallucinogens, are known for their ability to induce profound shifts in perception, cognition, and emotions. These compounds usher individuals into a psychedelic realm characterized by vivid visual hallucinations, heightened awareness, and deep introspection. Serotonergic neurotransmission, particularly the serotonin 2A receptor, appears to play a central role in mediating the effects of classic psychedelics. This receptor’s activation triggers a cascade of neural events that lead to the profound alterations in consciousness experienced during a psychedelic trip. Interestingly, some classic psychedelics bear structural similarities to serotonin itself, possibly contributing to their affinity for serotonergic receptors.

Further categorizing classic psychedelics reveals three distinct groups. Tryptamine derivatives, such as psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms) and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), evoke otherworldly experiences with mystical undertones. Phenylalkylamines, exemplified by mescaline (derived from the peyote cactus), are known for their profound impact on sensory perception and emotional processing. Lastly, ergoline derivatives, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), have captured the imagination of generations with their ability to unlock the mind’s deepest recesses. The history of these substances in the western world traces back to the early 1900s when mescaline research began, and the serendipitous discovery of LSD by Albert Hofmann in 1943 revolutionized the field of psychedelic research.

In contrast to their relatively recent recognition in the western world, classic psychedelics have been an integral part of traditional medicinal and spiritual practices in Central- and South America for millennia. Psilocybin, DMT (present in the ayahuasca brew), and mescaline (obtained from peyote and the san pedro cactus) have been revered by indigenous cultures for their healing properties and profound spiritual insights. These plant-derived substances have been used in rituals and ceremonies, forming an intricate tapestry of cultural heritage that dates back thousands of years.

On the other end of the psychedelic spectrum, atypical psychedelics offer their own unique journeys into altered states of consciousness. Though they share the ability to induce profound perceptual changes, atypical psychedelics achieve this through various molecular mechanisms and receptor profiles. Examples of atypical psychedelics that have demonstrated therapeutic potential in psychiatry include MDMA, an entactogen known for promoting empathy and emotional processing, and ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic that has shown remarkable efficacy in treating treatment-resistant depression and other mood disorders. Ketamine’s enantiomer, esketamine, has also garnered attention for its promising antidepressant effects.

As research into psychedelics progresses, society grapples with questions surrounding their safety, potential benefits, and appropriate use. Scientists, clinicians, and policymakers navigate a delicate balance between recognizing the potential therapeutic applications of psychedelics and addressing concerns about misuse and harm.

LSD

LSD, a semisynthetic derivative of lysergic acid, traces its origins back to the curious world of ergot fungi, specifically Claviceps purpurea, which thrives as a parasitic organism on rye and various grass types. This psychedelic compound is classified as an indole alkaloid, featuring a chiral structure, with only the d-isomer holding psychoactive properties. Pharmacodynamically, LSD exhibits a diverse profile, primarily acting as a partial agonist of serotonin 2A and 1A receptors. Additionally, it interacts with other serotonergic, dopaminergic D1 and D2, and adrenergic receptors. Such interactions contribute to the enthralling and mind-altering experiences reported by those who delve into the psychedelic realms induced by LSD.

In terms of potency, LSD commands attention. Even minute doses can produce subtle subjective effects, with the lower threshold for light experiences noted at approximately 5 µg p.o. For a full psychedelic effect, the common dosage typically ranges between 100 and 200 µg p.o. (approximately 1.4 to 2.8 µg/kg). The duration of these effects is dose-dependent, with reports of experiences lasting between 6 and 11 hours, sometimes even yielding lingering aftereffects.

It is crucial to acknowledge the potential risks associated with LSD use. The LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) of LSD varies between species, ranging from 0.3 to 60 mg/kg i.v. In humans, fatal overdose-related deaths linked to LSD use are extremely rare and are often connected to suicide or accidents resulting from increased risk-taking behavior while under the drug’s influence. However, there have been three reported cases with potential toxicity-linked deaths. As with any potent psychoactive substance, responsible use and harm reduction are paramount.

Psilocybin

Psilocybin, a remarkable and naturally occurring alkaloid, belongs to the tryptamine family and possesses a captivating chemical structure comprising an indole ring and an ethylamine substitute. Revered as one of nature’s most intriguing psychoactive compounds, psilocybin can be found in over 200 fungal species worldwide, with a prevalent presence in the genus Psilocybe. These fungi, commonly known as “Magic Mushrooms,” have captured the imagination of humans for centuries, inspiring ceremonial and spiritual practices among indigenous cultures across the globe.

Throughout South- and Central America, psilocybin-containing mushrooms hold deep cultural significance, especially among the Mazatec people, where they are revered as sacred entities. These indigenous cultures have long recognized the potential for profound mystical experiences facilitated by psilocybin, often employing these mushrooms in rituals to access altered states of consciousness, commune with the divine, and gain insights into the mysteries of existence.

A distinguishing characteristic of psilocybin is its prodrug nature. When ingested, it undergoes dephosphorylation, transforming into its active compound, psilocin. Psilocin’s profound effects arise from its high affinity for serotonin 2A receptors, among others within the serotonergic system. These receptor interactions trigger a cascade of neural events, leading to the transcendental experiences reported by users, including enhanced sensory perception, heightened emotions, and profound introspection.

The potency of psilocybin is striking. The effective dose range when taken orally typically lies between approximately 20 to 40 mg (approximately 0.3 to 0.6 mg/kg), with the duration of effects lasting around 3 to 6 hours. Within this temporal window, users often embark on inward journeys of self-discovery and connection with the universe, guided by the ethereal visions and transformative insights that arise during the experience.

Despite its potency, psilocybin exhibits a remarkable safety profile. In laboratory studies, the LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) for mice is reported at 280 mg/kg. In the context of human use, fatal overdose-related incidents are extremely rare. In the handful of cases reported, such tragic outcomes have been primarily attributed to accidents or increased risk-taking behavior while under the influence of the substance.

Mescaline

Mescaline, a captivating phenylethylamine, holds its roots firmly in the realm of nature, as it is derived from various cacti species, most notably the Central American peyote-cactus (Lophophora williamsii) and the South American san pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi). Throughout history, human civilizations have revered the mystical properties of peyote, with ritual use dating back an astounding 5,700 years. In the contemporary era, mescaline remains one of the few psychedelics legally permitted for religious purposes in the United States, preserving its sacred status.

Chemically, mescaline bears striking similarities to the synthetic atypical psychedelic MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine). However, unlike other classic psychedelics, mescaline’s primary mode of action centers on acting as a serotonin 2C receptor agonist, with a lower affinity for serotonin 2A receptors. Consequently, it exhibits a distinct and somewhat gentler psychedelic potency, with full effects typically requiring doses ranging from 200 to 400 mg (approximately 2.8 to 5.7 mg/kg). Once ingested, the mescaline experience unfolds over an extended period, with effects lasting around 10 to 12 hours, offering ample time for introspection and exploration.

In terms of safety, mescaline presents a reassuring profile. The LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) varies among different species, generally ranging from 50 to 157 mg/kg when administered intravenously. Importantly, there are no reported lethal overdoses in humans associated with mescaline use, offering reassurance to those who approach this sacred substance with respect and reverence.

The allure of mescaline lies in its unique ability to open doors of perception, guiding individuals into a realm of heightened sensory experiences, altered states of consciousness, and profound introspection. Its historical significance in religious practices and the continuity of its use in modern times showcase the enduring wisdom that cacti bestow upon humanity. As society rekindles its curiosity about the enigmatic world of psychedelics, responsible exploration and integration of mescaline’s teachings will play a crucial role in navigating the path towards understanding, healing, and transformation.

Ayahuasca

Ayahuasca, a revered plant-based brew, has been an integral part of religious rituals in indigenous communities within the Amazon region for centuries, with recent discoveries indicating its ritual use dating back at least 1,000 years in South America. This enigmatic concoction’s psychedelic properties arise from the unique combination of two key ingredients: the classic psychedelic compound DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine), commonly found in Psychotria viridis, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as harmaline and harmine, derived from the liana Banisteriopsis caapi.

The magic of ayahuasca lies in the synergy between DMT and MAOIs. When ingested orally, the MAOIs effectively inhibit the breakdown of DMT by MAO-enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract, allowing the potent tryptamine-based molecule of DMT to reach the brain and produce its profound effects. Structurally, DMT shares similarities with psilocybin and serotonin, and its powerful psychological impact is primarily mediated through agonism of serotonin 2A and 2C receptors, unlocking the door to extraordinary states of consciousness.

The composition of ayahuasca brews varies widely, as evidenced by analyses of samples taken from the Amazon region. The combination of DMT with harmine or harmaline results in a broad spectrum of potential dose combinations. In the plants used, the DMT content ranges from nine to 42 mg (approximately 0.1 to 0.6 mg/kg), while harmine doses span from 17 to 280 mg, and harmaline doses from 5 to 28 mg. The precise dosage and proportions utilized in the brews are often passed down through generations, guarded as sacred knowledge within indigenous traditions.

Upon ingestion, the effects of ayahuasca typically peak around 60 to 120 minutes, with a total expected duration of approximately 4 hours. During this transformative journey, individuals often report profound insights, emotional release, and a connection to the spiritual essence of existence.

While ayahuasca’s overall medical risks appear to be relatively low, it is essential to acknowledge that there have been rare lethal cases reported in the literature following its consumption. Despite this, there is no known LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) for ayahuasca. The safety and potential therapeutic applications of ayahuasca are subjects of increasing interest and research within the scientific community.

MDMA

MDMA, scientifically known as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, is a synthetic amphetamine derivative that has gained global recognition under the street name Ecstasy. This illicit substance is widely sought after for its euphoric, pro-social, and empathogenic properties, making it commonly referred to as an entactogen. However, due to its classification as a synthetic phenylethylamine, it also falls into the category of atypical psychedelics. The enthralling effects of MDMA stem from its complex interactions with neurotransmitters in the brain.

As a selective agonist at serotonin receptors, MDMA directly stimulates the release of both serotonin and norepinephrine, while also inhibiting the reuptake of these two neurotransmitters and dopamine. The involvement of serotonin 2A receptor agonism suggests that MDMA shares some phenomenological experiences with classic psychedelics. This unique combination of actions results in heightened emotional openness, increased sociability, and a sense of profound empathy.

The threshold for subjective effects of MDMA is typically around 50 mg, but the full spectrum of its effects is usually experienced within the range of 75 to 125 mg (approximately 1 to 1.7 mg/kg), with the experience lasting for approximately 5 to 7 hours. Users often report feelings of emotional connectedness, enhanced sensory perception, and an increased desire for social interaction during this time.

While MDMA exhibits relatively low toxicity in most animal species, with an LD50 ranging from 100 to 300 mg/kg, it is essential to approach its use with caution in humans. The expected LD50 in humans is estimated to be between 10 to 20 mg/kg. Tragically, multiple reports of lethal MDMA intoxications in recreational settings have emerged, primarily attributed to dehydration and combined drug intoxications.

As the allure of MDMA persists in recreational circles, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential risks associated with its use. Responsible harm reduction practices, informed decision-making, and moderation are paramount when exploring the realm of this enigmatic substance.

Ketamine

Ketamine, a synthetic cyclohexanone derivative, stands as a fascinating enigma within the world of pharmacology and consciousness exploration. Recognized as an essential medicine by the World Health Organization for its powerful anesthetic properties, ketamine’s multifaceted nature extends beyond its clinical use. Existing in a racemic form, it presents two possible configurations, (R)-ketamine and (S)-ketamine, with the latter displaying higher anesthetic potency.

Unique among anesthetics, ketamine takes an unconventional path by increasing haemodynamic parameters instead of suppressing them. Its distinct dissociative effects are characterized by a sense of detachment from the physical body, often leading to transcendent out-of-body experiences that intrigue users and researchers alike.

Beyond its role as an anesthetic, ketamine has garnered attention for its classification as an atypical psychedelic. The compound’s pharmacodynamic actions involve inhibiting glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in cortical regions, while also modulating gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A receptors and opioid receptors. This intricate interplay in the brain produces a range of effects, encompassing altered perception, sensory distortions, and a profound disruption of the ego’s normal functioning.

Ketamine’s clinical forms of administration are primarily intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal, with its oral bioavailability limited to a mere 17%. For psychedelic ketamine experiences, the common intravenous dose is typically around 35 mg (racemate, approximately 0.5 mg/kg) or 18 mg (esketamine, approximately 0.25 mg/kg), infused over approximately 40 minutes. The resulting psychoactive effects last anywhere from 90 to 120 minutes, during which users may traverse realms of consciousness seldom accessed through conventional means.

While ketamine boasts a relatively safe profile in medical settings, its recreational use demands caution due to potential risks. In animals, the lethal dose (LD50) exceeds 600 mg/kg, which translates to around 4 grams in humans. Nevertheless, there have been reports of lethal intoxications in humans, often associated with combined drug intoxications involving respiratory depressants, particularly impacting young males.

The multifaceted nature of ketamine has spurred interest in medical and scientific communities. Beyond its role in anesthesia, ketamine has shown promising potential in treating depression, particularly in cases that are resistant to conventional therapies, leading to the development of ketamine-based treatments. However, as with all potent substances, responsible use, informed decision-making, and appropriate medical supervision are imperative to mitigate potential risks.

Subjective effects

Psychedelic drugs, renowned for their profound psychoactive effects, elicit alterations in perception, affectivity, consciousness, and self, often culminating in transpersonal or mystical experiences. These transformative inner journeys are difficult to articulate due to their divergence from everyday conscious experience. In popular culture, the all-encompassing term “trip” is used to describe the inner odyssey people embark upon after consuming psychedelics. However, the onset and experience of these altered states of consciousness are not solely dictated by the substance; the psychological state of the individual and the surrounding environment also play pivotal roles, encapsulated by the terms “set” and “setting”.

The effects of psychedelics on sensory perception are diverse and mesmerizing. From subtle shifts in visual and spatial perception to synesthesia and vivid illusions of colorful, moving geometric patterns, users can experience a kaleidoscope of sensory wonders. These rich and intricate perceptual changes have long inspired artists, musicians, and authors, giving birth to the realm of psychedelic art.

Psychedelic experiences often accompany changes in mood, frequently leading to euphoria and heightened emotional sensitivity. Within supportive settings, these altered emotional states can facilitate profound emotional release and transformative breakthrough experiences. The emotional perception shifts brought about by psychedelics have been suggested as mechanisms underlying their reported antidepressant effects. Classic psychedelics tend to emphasize visual-aesthetic and transpersonal elements, whereas the atypical psychedelic MDMA primarily induces intense emotional-tactile stimulation, fostering feelings of euphoria, peace, and profound empathy.

Under the influence of psychedelics, the consciousness itself, including the perception of self and time, can undergo profound alterations. Some users report newfound insights into their own psyche, while others experience a sense of oneness with the environment, often described as mystical and transpersonal experiences. These effects have contributed to the use of psychedelic drugs in spiritual practices worldwide, as they allow individuals to transcend the boundaries of everyday reality and connect with higher entities. Insights and a shift from rigid self-focus to greater connectedness with the world are also regarded as significant mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of psychedelics. Ketamine, a distinct atypical psychedelic, produces dissociative alterations of consciousness and self, leading to derealization, depersonalization, and, in higher doses, out-of-body experiences.

Research investigating the subjective experiences of patients undergoing psychedelic treatments has identified overlapping phenomena of potential therapeutic significance. Across various studies involving patients with anxiety, depression, eating disorders, PTSD, and substance use disorders, the use of substances such as psilocybin, LSD, ibogaine, ayahuasca, ketamine, and MDMA has elicited insights, altered self-perception, increased connectedness, transcendental experiences, and an expanded emotional spectrum.

While psychedelics can offer transformative experiences, they may also lead to acute psychological complications and adverse effects, commonly referred to as a “bad trip.” Symptoms of disorientation, panic, fear, and overwhelming distress can arise, especially in challenging settings. Nevertheless, despite such adverse reactions, many individuals report benefiting from the experience, highlighting the complex interplay between potential challenges and personal growth.

Mechanisms of action

The mechanisms of action of psychedelic drugs are complex and not fully understood, but they generally involve interactions with various neurotransmitter systems in the brain. Different psychedelics may have distinct mechanisms of action, but some common features can be identified:

- Serotonergic System: One of the primary mechanisms of action for many psychedelics involves their interaction with the serotonin system. Classic psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline primarily act as agonists at the serotonin 2A receptor (5-HT2A), leading to increased serotonin signaling. This activation of 5-HT2A receptors is thought to be a key factor in producing the characteristic psychedelic effects, such as alterations in perception, consciousness, and self-awareness.

- Glutamatergic System: Ketamine, an atypical psychedelic, exerts its effects through the modulation of the glutamatergic system. It is an NMDA receptor antagonist, which means it blocks the action of the NMDA receptor, a type of glutamate receptor. This leads to increased glutamate levels and disrupted glutamate signaling, resulting in dissociative effects and alterations in consciousness.

- Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Systems: Some psychedelics, including MDMA, influence the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems in addition to serotonin. MDMA is known to stimulate the release of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, leading to its characteristic empathogenic and stimulant effects.

- Default Mode Network (DMN) Modulation: Studies have shown that psychedelics, especially classic psychedelics like psilocybin, can lead to decreased activity in the brain’s default mode network (DMN). The DMN is associated with self-referential thoughts, introspection, and mind-wandering. By dampening DMN activity, psychedelics may disrupt rigid patterns of thinking and foster new perspectives and insights.

- Neuroplasticity and Synaptic Connectivity: Psychedelics have been suggested to promote neuroplasticity and alter synaptic connectivity in the brain. This could be linked to their potential therapeutic effects, such as the treatment of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Entropy and Increased Brain Complexity: Studies have found that psychedelics increase the entropy and complexity of brain activity, potentially explaining the diverse and often unpredictable experiences reported by users.

The effects of psychedelics can vary depending on factors such as dosage, individual differences, set and setting, and the specific psychedelic compound used. As research progresses, a deeper understanding of these mechanisms may pave the way for the development of novel therapeutic approaches and a more comprehensive comprehension of the human brain and consciousness.

Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression

Unipolar and bipolar depression are prevalent and challenging mental health conditions that significantly impact the lives of millions of people worldwide. Traditional treatments, such as antidepressant medications and psychotherapy, are effective for many individuals, but a substantial number of patients do not achieve full remission or experience intolerable side effects. This treatment-resistant population has spurred interest in alternative therapeutic approaches, leading to the exploration of psychedelics as potential options for managing depression.

In the 1950s to 1970s, several studies explored the potential antidepressant effects of classic psychedelics such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, due to the lack of double-blind, placebo-controlled designs in these early investigations, the overall efficacy in reducing depressive symptoms should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, the results indicated a positive signal for their potential as antidepressants.

The international ban on psychedelics halted clinical research with these substances until the early 2000s, when a revival in psychedelic research began. Clinical studies investigating psychedelics in psychiatric conditions with affective symptoms, including depression, were initiated. One of the first investigations examined the effects of a single dose of psilocybin as an adjunct to psychotherapy in patients with cancer-related anxiety and depression. The study demonstrated significant symptom reduction, which remained measurable in a substantial percentage of patients at a 6.5-month follow-up. The psilocybin-induced mystical experience was identified as a crucial mediator of the therapeutic effect.

Subsequent studies further explored the antidepressant properties of psilocybin, ayahuasca, and LSD. Research on ayahuasca indicated potential antidepressant properties in both healthy volunteers and patients with depression. Similarly, LSD showed beneficial effects in patients with life-threatening diseases, leading to a sustained reduction of anxiety.

A four-step treatment approach has been developed for studies with unipolar depression, including assessment, preparation, the psychedelic experience, and integration. Studies employing this approach with psilocybin and ayahuasca in patients with treatment-resistant depression demonstrated promising results, with high response and remission rates. However, some limitations, such as small sample sizes and potential expectancy effects, must be considered.

While the potential of classic psychedelics in treating unipolar depression shows promise, it is essential to address safety concerns, particularly in patients with bipolar disorder. Some reports suggest that psychedelics may induce manic switches in this population. Thus, rigorous screening and monitoring are crucial to ensure patient safety.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy has shown promising results in treating severe PTSD, but its potential in depression treatment remains to be explored. On the other hand, ketamine, an atypical psychedelic, has already been established as an effective and rapid-acting antidepressant in both unipolar and bipolar depression.

Conclusion

The field of psychedelic research for the treatment of depression, particularly unipolar depression, has shown promising results. Studies on classic psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline have demonstrated potential as rapid and effective antidepressants, albeit with the need for larger and more rigorous clinical trials to establish their efficacy definitively.

The use of ayahuasca and MDMA has also shown positive outcomes in treating depression, especially in the context of therapy. However, more research is needed to explore their full potential and safety, particularly in patients with bipolar disorder, where manic switches have been reported in some cases.

Ketamine, an atypical psychedelic, has emerged as a well-established and rapid-acting antidepressant for both unipolar and bipolar depression. Its use has been incorporated into treatment guidelines and has shown efficacy in various administration routes, including intravenous and intranasal.

As the field continues to evolve, it is crucial to establish standardized treatment protocols, rigorous safety measures, and thorough screening procedures to ensure patient well-being and maximize the therapeutic benefits of these substances. The importance of a comprehensive treatment approach, including assessment, preparation, the psychedelic experience, and integration, cannot be understated.

While the potential of psychedelics for depression treatment is exciting, responsible exploration and cautious implementation are essential. As further research unfolds, the integration of these substances into mental health treatment paradigms could open new possibilities for those suffering from depression, offering hope for a more effective and transformative approach to mental health care.